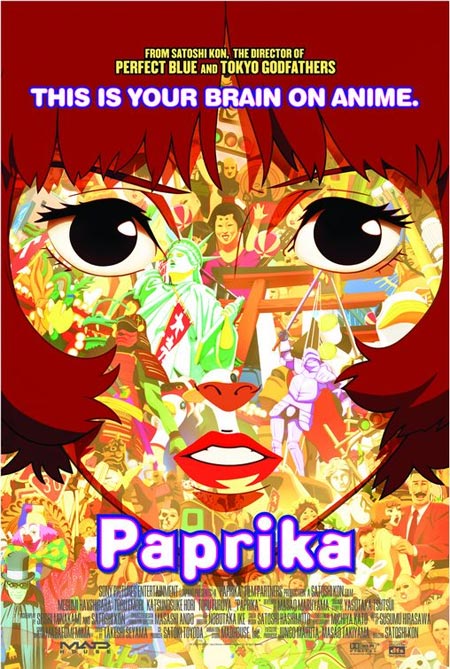

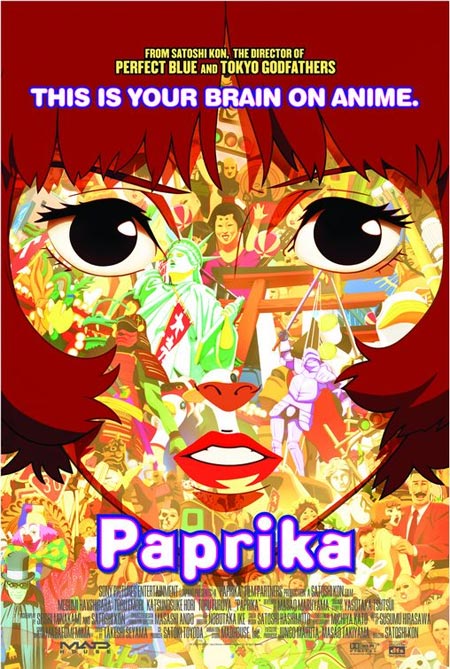

At first glance, Paprika is a stylish sci-fi detective thriller that uses dreams as a reason to explore the limits of animation. The visuals are exhilarating and titillating based on any level of criteria. But while many would be quick to write this film off as another “beautiful but brainless” offering from Japan, underneath all the sheen lies a fascinating and incredibly honest exploration of the joys and troubles of filmmaking. Paprika is an incredibly joyous film, multi-faceted and brimming with ideas, and it might be the best animated feature of the year.

Satoshi Kon has always been one of the brightest stars in anime, leaving his mark with works such as the almost flawless Perfect Blue and the heartwarming Tokyo Godfathers. His character designs are a sophisticated blend of classic caricatures and modern sleekness, rounded out with a sardonic edge that hints at something beneath the surface of every character. His films tackle subject matter not typically seen in Japanese animation, such as the deification of pop culture and the disease of social isolationism. But, as accomplished as they may be, his movies all have common flaws. They tend to lose their focus: sometimes exploring ideas too freely and not finding a clean path out, other times wrapping up too quickly and leaving loose ends behind. It’s as if he’s fighting against the clock (or perhaps the budget) – playing freely with the ideas for a while, but then suddenly rushing to a premature finale at the expense of cohesion and clarity. To some, his struggles might be a sign of stubbornness and a man unwilling to develop as a filmmaker at the expense of his imagination. But, as Paprika illustrates, this may not necessarily be the case.

The director’s latest film tells the story of a researcher, ice queen Dr. Atsuko Chiba, her device, the DC mini, and her alter-ego, the bubbly Paprika. Dr. Chiba uses the DC mini to lucidly traverse the dreams of her patients, helping them understand their own subconscious minds and the fears that dwell within them. However, the DC mini is far from complete and even further from government approval, which means she must adopt an alternate persona to accomplish her work. After one of a number of successful treatments, she returns to the lab the following day to find that someone has stolen the DC mini, using it for mass subconscious terrorism and altering the psyches of the people whose dreams he touches. It’s up to Atsuko (and Paprika) to track down the terrorist and restore order to both the dream world and the real world.

The centerpiece of the film, a large, noisy parade of souvenir shop trinkets and household appliances, marches aimlessly through the minds of people affected by the corrupted DC Mini. But this cacophonous celebration is not the terrorist’s desired result. It is the grotesque side effect of multiple streams of thought becoming a river of confusion – a Frankenstein’s monster of dreams. The parade, in a sense, is a Satoshi Kon film in itself. It represents Kon’s own creative instinct – a lush, innocent spectacle that gradually becomes something unmanageable and devoid of context or meaning. By personifying his own filmmaking process in this film, he effectively exposes his own artistic flaws for his characters, and the audience, to see. Even on first impressions, Dr. Chiba shudders at the nightmarish mass, speculating that it exists only to march towards the end of existence. Paprika and her cohorts are in constant battle with the parade throughout the film, struggling against it for control of their own consciousnesses and trying to contain it for the good of humanity. Kon battles in the same way with his own imaginative impulses of trying to wrangle in a rogue creation. In Japan, where animated film is definitely not a niche market, there are expectations that come with being recognized as one of the best in the business. While Satoshi Kon is well-respected, he has always desired the sense of commercial success that has evaded him time and time again. In an interview with the Washington Post, Kon states that he enjoys movies that are mostly understood, but still interpretable. It’s obvious from viewing any of his past works that there is a delicate balance between making disposable eye candy and making a meaningful film. Though he has yet to master that balance, it’s a conscious and fruitful struggle.

Detective Konakawa’s subplot provides another interesting angle to the story. As the film’s primary “patient,” Konakawa has his dreams visited by Dr. Chiba on more than one occasion. In his consciousness lies the history of film itself, comprised of scenes from Tarzan movies, film noir, romance films and more. It’s very reminiscent of what Satoshi Kon did in Millennium Actress, a sentimental tribute to the rich history of cinema. What’s interesting here is that Mr. Kon takes this side character, typically the cool and collected yet otherwise unremarkable cop, and injects him with some of his own blood and soul. As he discusses with Paprika in his dreams, Konakawa’s restlessness stems from a conflict between his love for cinema and his past failure as a creator. Sound familiar? In the end, Konakawa abandons his film aspirations, betraying his old friend and collaborator (who may or may not be Konakawa himself). This proves to be so painful that he can’t bear to watch movies he once loved. While Kon’s reaction to his own shortcomings may not be as extreme, they’re rooted in similar feelings.

Another fascinating moment of self-criticism appears later in the film. During an argument with Dr. Tokita, the morbidly obese genius who designed the DC Mini, Dr. Chiba exclaims that Tokita is exactly like the psychotic Himuro, Tokita’s former research partner and the main suspect in this mess. Both are unable to relate to the real world, Tokita because of his physical state and his child-like mind, and Himuro because of his repressed homosexuality. To compensate, both drown themselves in their hobbies, oblivious to the results of their actions and the responsibilities that follow. Mr. Kon has tackled themes of geek obsession before, damning it in his television series, Paranoia Agent. But in this instance, his tone seems more empathetic than cautionary. The same way the Japanese youth are obsessed with toys, games and cartoons, Satoshi Kon is obsessed with film. Time and time again, Kon has had troubles balancing what he wants to do (create fantastic dreamscapes and explore the modern human condition) with what he has to do (make a movie with a flowing progression).

Paprika doesn’t quite succeed in this respect; the ending does seem somewhat thin, and the audience is asked to blindly follow what is being laid out for them. Kon lays the sentimental flavor on a bit too thick, possibly hoping that the viewers might forget that some of the dangling ends were left untied. Nonetheless, Paprika is Satoshi Kon’s strongest effort. It stretches the boundaries of the genre while celebrating life, film, and the joy of innocence. The honesty and the transparency of the movie make it a fascinating window into the filmmaker’s mind – kind of a subtle, real-time commentary on his approach to the film as it plays. While his past films have left a residue of dread or perhaps uncertainty, Paprika is a celebration and leaves you with a feeling of pure joy. Paprika successfully delivers its message: dreams are important and shouldn’t be suppressed, and while life is full of responsibility, a little spice is always a good thing.